Tonto Natural Bridge

Massive travertine formation in central Arizona

Published on Wednesday, 29 November 2023. Revision 0.

.jpg)

Contents

Tonto Natural Bridge

Massive travertine formation in central Arizona

Published on Wednesday, 29 November 2023. Revision 0.

The diversity of natural features our country offers will never cease to amaze me.

Tucked deep within a deep canyon just two hours northeast of Phoenix lies one of Arizona’s countless impressive natural features. Pine Creek quietly flows, babbles, and trickles it way through a classic sheer-walled gorge that the American West is famous for. About halfway through its course the creek flows through the largest natural bridge in the world: Tonto Natural Bridge.

Over 400ft long, and averaging well over 100ft wide and 100ft tall, this “bridge” is the remnant of a large cave passage the roof of which has since collapsed leaving only a short segment. The springs which deposited the rock the bridge is formed in still flow producing ribbon like waterfalls over the downstream entrance which twist and dance in the wind that howls through the canyon.

Originally known by Indigenous Peoples, the bridge was first discovered by settlers near the end of the 1800s. David Gown established a homestead on top of the bridge which lasted beyond his death and into the 1950s when descendants sold the land to a family which eventually sold the land to the Arizona State Parks. The original lodge still stands as the main Visitor Center. Today the Bridge is the focal point of Tonto Natural Bridge State Park which hosts trails and interpretive features for the plants and animals which live in this environment.

A couple of years ago a long time friend of mine, Micah Kipple, became a park ranger at this state park and had been inviting me to come out for some time. In August of this year Hope was doing field work in Arizona for a week, and I had flight credits to use. The stars aligned, and thus off we went.

Visiting Tonto Natural Bridge

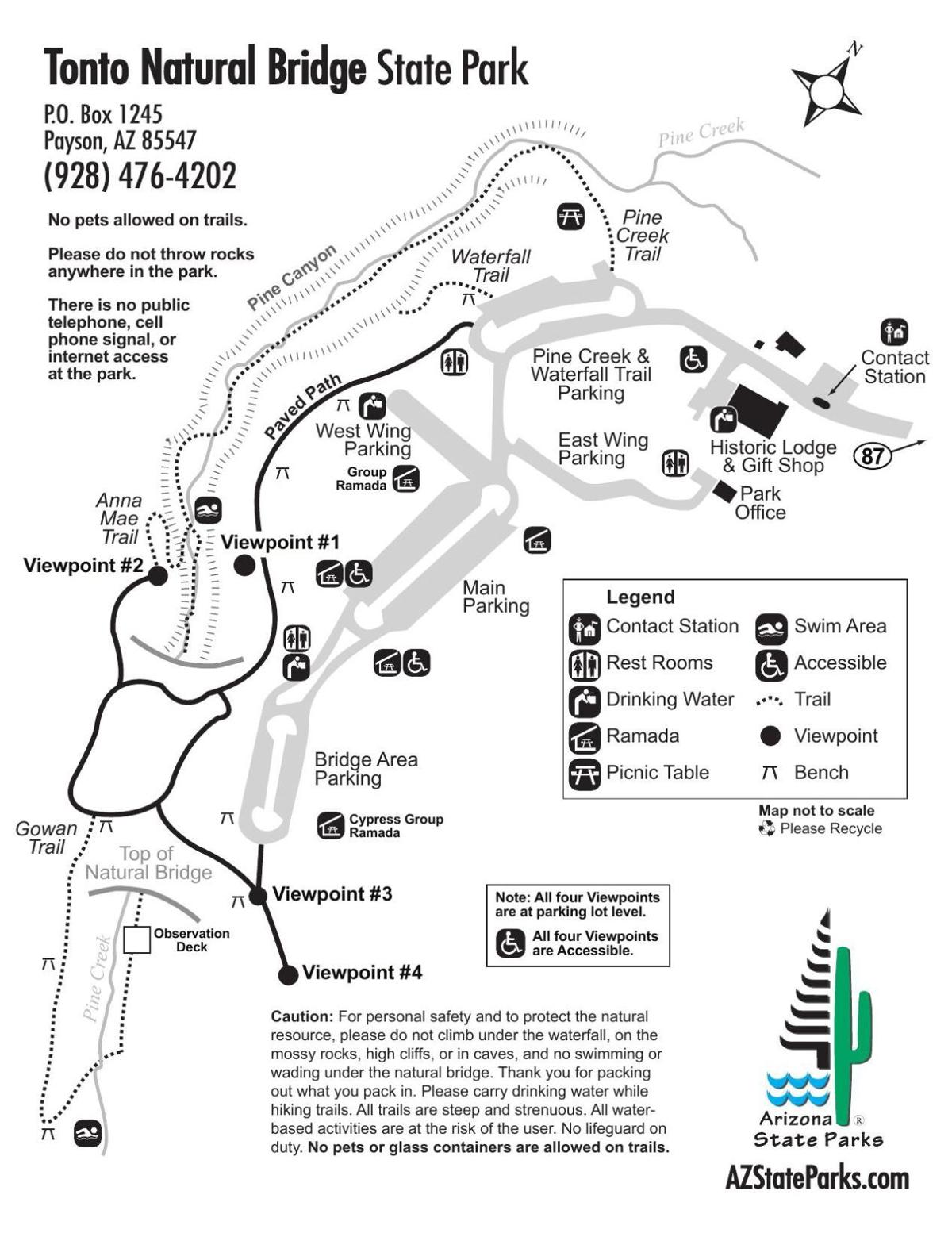

Tonto Natural Bridge is located within Pine Creek Gorge approximately 100 miles northeast of Phoenix, Arizona. The Bridge is accessed by a road which snakes its way down the sheer walls of the gorge from State Route 87 about halfway between the small communities of Pine and Payson. This road is very steep – make sure you know how to ride your lowest gears or you’ll burn your brakes up.

Tonto Natural Bridge is undoubtedly one the most spectacular karst features in the United States, if not the Western Hemisphere. The bridge spans roughly 150ft in width and 180ft in height and is just shy of 400 feet long. Formed in travertine, the underside of the bridge is a menagerie of active and dead cave formations. The travertine mound itself is a karst environment and several small caves are visible on the cliffs surrounding the bridge. Springs emanating from the travertine still flow year round and cascade off the travertine walls and plunge over the downstream end of the bridge in a ribbon of water that twists and dances in the near constant wind that funnels through the underside of the bridge.

Several trails provide access to the bottom of the bridge, all of which are very primitive and rugged. I want to emphasize primitive and rugged. In many places the trail is simply arrows on boulders pointing the way ahead while you scramble and climb over rocks and boulders in the creek bed. Solid footwear is an absolute necessity.

My favorite trail was the Pine Creek trail which loops from the upper parking lots down into Pine Creek Gorge and then under the Bridge. This trails is the longest in the park and allows one to see Pine Creek Gorge before, during, and after its interaction with the travertine being deposited. Just upstream of the bridge itself is a waterfall which drops over the side of the travertine bridge which is accessible by its own short trail. Also in this area is a small cave along the trail which visitors can walk into.

The underside of the Bridge is shaded and much cooler than the surrounding gorge. Wind blows up and down the gorge and the falling water from above is such a fine spray that it’s often impossible to stay completely dry under the bridge.

To Build A Bridge, the Geology History of Tonto Natural Bridge

The Waterfall Trail brings one to a waterfall where the active springs discharge over the edge of the travertine terrace. Here one can see the deposition in action. Up under ledges here you can see the intricate structures of the travertine.

The gorge is formed roughly along a boundary between very old and hard igneous rocks and younger and softer sedimentary rocks. Springs discharging partway down the gorge have deposited billions of cubic feet of travertine and formed a large and flat terrace that spans the width of the gorge.

Standing under the bridge and examining it with a critical eye brings one to the understanding that its geologic history is one of chaos and confusion. The travertine is being deposited at very high rates – up to 1.5 inches per year in some areas. As the travertine deposits it traps rocks, vegetation, and other debris within it. This debris becomes part of the rock unit until it’s later exposed by the erosive forces of Pine Creek. This also means that the bridge didn’t form along any one specific fault line or joint or other weakness but rather followed a mess of cavities and fractures from the embedded debris. Evidence abounds of the bridge’s geologic history of having travertine deposit, then get washed away, the deposit again. Gravel beds from the ancient Pine Creek are visible 50ft or more above the base of the bridge cemented in place.

Under the bridge one can see the various rock units involved in the geologic history of Tonto Natural Bridge by examining the cobbles in the creek bed and plunge pools.

The speleologic chaos of the Bridge inspired me to do some deeper digging into it’s geologic history. Written literature was far and few between. Thankfully, my friend Micah Kipple was both a park ranger with access to park materials and a background in geology and was able to flesh out the story for me. In lieu of writing it all out I made a slideshow of sorts that you can flip through. It covers the geologic history of the bridge from 1.7 billion years ago to its inevitable future.

A Brief History of Tonto Natural Bridge

Indigenous peoples have used the bridge for at least the last 11,000 years with the most heavy presence coming after 3000BCE. Most sites within the park itself date to around 1200CE and are of mixed Hohokam and Sinaguan origin. Around 1700 the Tonto Apache began using the area for seasonal living and farming of maize. This lasted until 1866 when the US Army discovered the bridge and forcefully removed the Tonto Apaches.

Local lore is that in 1877, David Gowan was hiding from local Apache when he stumbled upon the Bridge. The beauty of the bridge and suitableness for a homestead inspired him to homestead. Gowan has emigrated from Scotland and in the late 1890s a travelling journalist wrote about the bridge in a local newspaper. Gowan’s nephew read the article, correctly surmised the familial connection, and wrote to his uncle. Gowan sold the land to his nephew after the latter emigrated with his family – sight unseen – to the property. There the newphew built the lodge which is still used today.

Two generations later the property was sold to Glen Randall whose estate held it until the 1960s when prolonged negotiations began to acquire the property by the state. By this point the property had already been largely developed into a park, albeit a privately owned and operated one. The bridge’s location, existing infrastructure, and scenery made it attractive to many developers as a potential business opportunity and the state had to compete with all interested parties. This first round of negotiations went as far as the passage of an appropriations bill by the state legislature before failing. Complicating matters was an uncertainty in ownership that was not cleared up by the courts until the late 1980s.

In 1989 the state was approached by the owners of the property and a second round of negotiations began. Less than a year later the state purchased the property. Less than a year after that the park had opened with new roads, picnic facilities, and staff infrastructure.

The Flora and Fauna of Tonto Natural Bridge

The perennial water source of the spring makes the Tonto Bridge area a lush and diverse ecosystem. It is an oasis within the largely dry and arid deserts surrounding it. The vegetation around the bridge is largely comprised of various trees and shrubs such as oaks, cottonwoods, sycamores, junipers, and pinyons. Pine Creek Gorge is deep enough that a knowledgeable observer can see the changes of dominant trees and shrubs with different elevations and rock units. The water source for the springs provides a perennial source for ferns and mosses such as the black maidenhair fern found near the waterfalls.

The plants that thrive in this location feed a large and diverse population of animals. The park is a haven for deer, skunk, rodents, and javelina hogs. Spending time there in the evening allowed me chances to photograph animals such as the blonde tarantula, the Arizona bark scorpion, pallid bats, rattlesnakes, and the giant desert centipede (granted, that one was dead).

Switch between different light sources for the bark scorpion:

Closing Remarks

Tonto Natural Bridge is one of the gems of central Arizona, and I am glad I had a lot of time to spend there. As a naturalist the geology alone was something that I spent days observing and pondering. I would like to return to do more of this. If you're to visit Tonto there are a couple things worth noting. First and foremost, the trails and rugged and hard. You will be climbing on things - tall and slippery things. It is very hot, you will get very hot and dehydrated even with ample amounts of water. Bring more than you think you need, take your time, and enjoy the environment.

References

This is a bit different than my usual references section. All information in this article pertinent to the history of Tonto Natural Bridge was sourced either by personal correspondance with Micah Kipple or from the park history of Tonto Natural Bridge (most of which was written up by Kipple based on his own research and literature review). The geology is much the same, largely from direct correspondance with Kipple and then I made the graphics myself.